For the 16 Days of Activism Against Gender Violence, Mary Tomsic explores cinematic representations of physical and sexual violence against women in We Aim to Please, a 1970s Australian feminist film.

As a historian, representations of complex ideas in art and visual sources continually impress me. Compelling creative arguments, so economically made in artistic endeavours, entice me to them as historical artefacts. Judy Horacek’s cartoon “Not asking for it” (2014) about “non-provocative” behaviour and dressing; the Guerrilla Girls’ feminist art campaigns from 1985 to the present; and Tracey Moffatt’s photographic series “Something More” (1989), “Scarred for Life” (1994) and “Scarred for Life II” (2000) are forceful examples of critical creativeness.

I examined many cases of Australian women’s innovative cultural and political expression while carrying out research into women’s work and leadership within filmmaking and film culture.

One particularly arresting experimental film that speaks to the issue of gender violence is Margot Nash and Robin Laurie’s We Aim to Please (1976). The short film explores ideas about gender, sex, desire and violence while also questioning the operation of cinematic spectatorship in society.

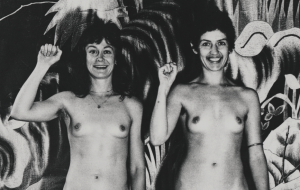

The film begins and we hear the question “is the camera rolling?” We see Nash and Laurie standing naked in front of the camera, initially laughing. They read a statement together describing their situation – the dangers, madness, isolation and defencelessness, what they had been taught and by whom: “We didn’t know, but we’re finding out fast.” With boldness, strength and humour they declare, “When we do find out” “Watch out!” Audio and visual aspects of the film is purposefully disjointed, with fragmented images presented throughout its thirteen minutes. Close up shots of filmmakers’ lipstick-painted lips directly address the viewer saying the “ideal spectator is always assumed to be male and the image of woman designed to flatter him” (view clip here).

Nash and Laurie put on make up in an exaggerated manner, rendering them more like unkempt clowns than “pretty” and “feminine” women. Sequences such as this are at times playful, and also have serious consequences. In a later scene the filmmakers, one at a time, look directly at viewers, smiling, laughing, staring, licking lips and wiping faces while the sounds includes laugher, moans and repeating the word sex to the accompaniment of a jackhammer in the background. Towards the end of this we hear one of the filmmakers making increasingly aggressive demands for the women onscreen to smile. “Come on smile, fuck you” is the final one; the women onscreen don’t look away (view clip here).

Vulnerability and violence are present throughout the film. One particularly brutal scene presents an unseen person wielding a beer bottle, viciously attacking and destroying a watermelon that has “FUCK ME” written on it. The accompanying audio isn’t clearly decipherable; it seems to be, in part, a scratchy CB radio exchange in which we hear male voices and reference to being at the “Royal Melbourne Hospital” and “police will be there as soon as possible.” I find this representation of violence stark; the obscured sound, worrying.

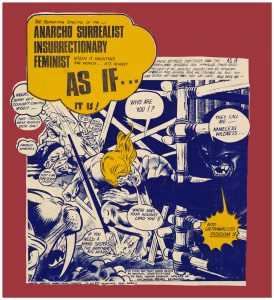

But as Susan Lambert notes, viewers are not left “feeling frightened and powerless”; rather, the filmmakers shout “that they won’t be intimidated and are determined to change the power relationships inherent in capitalism and sexual politics” (from Curator’s Notes for Clip 2). The film’s response to the violence, in part, captures the energy and excitement of the era in which the film was made. Robin Laurie has recently spoken about the insurrectionary nature of the late 1970s. Laurie told of her and Nash’s interest in feminism, history and surrealism and how they could, at the time, be fearless and unafraid in their political activism (audio online here).

Towards the end of We Aim to Please the audience witnesses close ups of the filmmakers’ body parts, of breasts and genitals, surrounded by plants. There is laughter and jokes when plants and genitals mix, and curiosity when they discuss their labia – comparing sizes and the suggestion given to one of their sisters that hers required plastic surgery because it was “too long and ugly.” We also see a hand, with dirt-filled nails, caressing a breast. We do not know whether this hand and breast are part of the same body, or if the hand belongs to a different body, that of the other filmmaker.

This creative and critical exploration of the relationship between sex and particular types of possible violence against women is a valuable historical artefact. The short film has been awarded prizes, screened around the world, and can be viewed at the Australian Centre for the Moving Image’s Mediatheque in Melbourne. This creative representation, made in the 1970s, spoke to particular issues at the time, and did so using now not so “new media.” Greater accessibility to filmmaking equipment facilitated by the Australian government’s support of filmmaking enabled those involved with the second wave feminist movement to work on the task of using “the film medium for [our] own ends, to promote and confirm non-exploitative ways of being.”

The purpose of the 16 Days of Activism Against Gender Violence Campaign is to raise awareness about violence against women and its impact on a woman’s physical, psychological, social and spiritual well-being. In their 1976 work, filmmakers Nash and Laurie have achieved this purpose; and in so doing, they also brought forth feminist analysis, action and humour. While We Aim to Please is art that is about more than violence alone, the violence against women examined in it reflects on the impact of violence on particular and individual women, possible responses to this alongside broader social forces in operation. It is vital that, as historians, we use this contemporary campaign to highlight the critical and creative historical activism that precedes it.

~

CASA House at The Royal Women’s Hospital, Victoria, provides support and care for victims and survivors of sexual assault. To donate, click here.

Mary Tomsic is a Postdoctoral Research Associate researching visual representations of child refugees as part of the ARC Kathleen Fitzpatrick Laureate Fellowship on Child Refugees and Australian Internationalism from 1920 to the present at The University of Melbourne. Mary’s broad teaching and research interests are in cultural history in particular visual culture, film and history; historical representations in popular culture; Australian film culture and understandings of gender & sexuality. Her most recent publication is a co-edited collection Diversity in Leadership: Australian women, past and present (with Joy Damousi and Kim Rubenstein, ANU Press 2014).

Mary Tomsic is a Postdoctoral Research Associate researching visual representations of child refugees as part of the ARC Kathleen Fitzpatrick Laureate Fellowship on Child Refugees and Australian Internationalism from 1920 to the present at The University of Melbourne. Mary’s broad teaching and research interests are in cultural history in particular visual culture, film and history; historical representations in popular culture; Australian film culture and understandings of gender & sexuality. Her most recent publication is a co-edited collection Diversity in Leadership: Australian women, past and present (with Joy Damousi and Kim Rubenstein, ANU Press 2014).

Follow Mary on Twitter @mary_tomsic.

Copyright remains with individual authors who grant VIDA holding a perpetual, world-wide, royalty free and non-exclusive license to use, distribute, reproduce and promote content. For permission to re-publish any VIDA blog post, in whole or in part, please contact the managing editors at auswhn@gmail.com.au