The VIDA blog Inspirational Women series continues with the life of Persia Campbell, a once-renowned Australian economist in the United States.

On a spring evening in 1974, an elderly resident of Queens, New York was found unconscious on her kitchen floor. She was rushed to hospital, and died of a stroke soon after. In the weeks that followed, her children received expressions of condolence from around the world. After the New York Times published a eulogy, tributes poured forth from Buenos Aires, Auckland, Geneva, London, and Washington D.C., bearing letterheads from the International Federation of University Women (IFUW), UNICEF and the U.S. federal government. The authors were more than usually generous in their praise. ‘I admired her extravagantly’, confessed IFUW president Elizabeth May; she was a ‘legend’ at the London School of Economics noted economist Allan Fisher. ‘[She] was held in the highest regard and affection by all of us the United Nations who had the pleasure of working with her’, recalled Gilberto Rizzo. She was a ‘highly revered colleague’, a ‘truly remarkable woman’, who ‘was fortunate to die at the pinnacle of her career’.

Although this woman died in New York and was mourned in high places throughout Europe and the Americas, her life began far from the world’s halls of power. Her name was Persia Campbell, and she was born to schoolteachers in Australia, in regional New South Wales, during the last gasp of the nineteenth century. Campbell became an economist, internationalist and UN lobbyist, whose career was dedicated to ‘foster[ing] higher living standards across the world’.

Unlike most mid-twentieth-century economic experts, who championed rapid economic growth as the key to successful development, Campbell scorned the logic of ‘growthmanship’. In her view, the prevailing emphasis on production-oriented metrics such as Gross National Product (GNP) was misguided. It obscured the need to prioritise standards of living. People, not numbers, were at the heart of her idea of global ‘progress’. Yet while Campbell’s promotion of social and economic justice spanned six decades and five continents, leaving powerful legacies upon international development and consumer economics, her career is today little known in Australia. Once a rising star of the local intelligentsia – and one of the few female economists of her generation – she has since slipped under the radar of both economic and gender historians.

Born in Nerrigundah on March 15, 1898, Campbell was educated at Sydney’s academically rigorous Fort Street Girls’ High School and entered the University of Sydney in 1915. There she imbibed the progressive thought that made early-twentieth-century Australia the world’s foremost ‘social laboratory’. Her decision to specialise in economics owed much to World War I, which raged throughout her undergraduate years. After witnessing the conflict, she became ‘seized with the desire to “do something” to prevent a second world war’. According to her analysis of the war and its aftermath, ‘economic matters’ held the key to lasting peace. After completing undergraduate and Masters degrees in economics under the tutelage of leftist firebrand Professor Robert Irvine, Campbell won a scholarship to continue her studies at the London School of Economics in 1920.

In London, Campbell studied under Fabians Harold Laski and Graham Wallas, and socialised with prominent internationalists such as Helena Swanwick. By 1921, she was convinced of the imperative ‘to establish relations between Eastern and Western civilisations on terms acceptable to both’. In her MSc thesis, a British Empire study of Chinese labour, we can also find early traces of concern for economic and social justice. Published as Chinese Coolie Emigration (1923), the study concluded that immigration policies should prioritise the ‘welfare of man’ and the ‘satisfaction of normal human wants’. Most provocatively, Campbell was explicit that these ‘wants’ should be met among both the British and the Chinese. And although a mere ‘colonial lass’ of only twenty-three, Campbell was already turning heads with her combination of intellectual precocity and unshakeable poise. ‘I wish she were not a bird of passage’, Swanwick wrote. ‘I don’t know that I have ever met such a combination of personal charm with scientific accuracy and learning’. LSE Director William Beveridge was likewise impressed, and became a stalwart champion of her work.

In London, Campbell studied under Fabians Harold Laski and Graham Wallas, and socialised with prominent internationalists such as Helena Swanwick. By 1921, she was convinced of the imperative ‘to establish relations between Eastern and Western civilisations on terms acceptable to both’. In her MSc thesis, a British Empire study of Chinese labour, we can also find early traces of concern for economic and social justice. Published as Chinese Coolie Emigration (1923), the study concluded that immigration policies should prioritise the ‘welfare of man’ and the ‘satisfaction of normal human wants’. Most provocatively, Campbell was explicit that these ‘wants’ should be met among both the British and the Chinese. And although a mere ‘colonial lass’ of only twenty-three, Campbell was already turning heads with her combination of intellectual precocity and unshakeable poise. ‘I wish she were not a bird of passage’, Swanwick wrote. ‘I don’t know that I have ever met such a combination of personal charm with scientific accuracy and learning’. LSE Director William Beveridge was likewise impressed, and became a stalwart champion of her work.

After leaving London, Campbell held a brief research fellowship at Bryn Mawr College in Philadelphia, USA before returning to Australia. There, she joined a new cadre of interventionist economists determined to use their training to guide and better society. At the NSW Industrial Commission, where she worked from 1926, Campbell engaged in front-line research on wages and living costs that marked the beginning of her consumer consciousness. From this point onward, the individual household and its capacity to attain – or not – an appropriate ‘standard of living’ would be at the heart of her economic worldview. The embryonic interest in ‘human wants’ evident in her LSE thesis had flourished into a full-blown fixation.

It was also in these years that Campbell began to insist that the material comforts commonplace within Australia’s borders be extended worldwide. She was, by the mid-1920s, a prominent local internationalist, active within the League of Nations Union, the Pan Pacific Women’s Association and the Institute of Pacific Relations. In such arenas, Campbell advocated the internationalisation of the Australian welfarist model. Most frankly, in a 1927 speech to the League of Nations Union in Sydney, she bemoaned the ‘low standard of living in Asiatic countries’, and insisted that ‘standards of living in the Pacific countries should be raised, and not lowered, to one level’.

Campbell’s life took an abrupt turn in December 1929, when she took up a fifteen-month Rockefeller Fellowship to study agricultural policy in the United States. Two days before she was due to return home, Campbell announced she had consented to marry local engineer Edward Rice and make her home in New York. The couple wed in 1931, and had two children in quick succession. But marriage and motherhood did little to constrain her professional energies. In 1930s America, the economic hardships of the Depression had given rise to a thriving consumer movement, and here Campbell founded a congenial home. She helped found the ambitious but short-lived Consumers National Federation, and also pursued consumer questions at a theoretical level via a Ph.D. in public law at Columbia University. Her dissertation, published in 1940, was a study of New Deal consumer representation that insisted U.S. national policy be directed ‘towards the goal of a better living standard for all’.

In 1939, when the outbreak of war put paid to her much-loved League of Nations, Campbell’s private life also imploded. That year she was widowed, and the income from her husband’s estate soon dried up. Faced with little support and less money, she commenced full-time work as an Assistant Professor in Economics at Queens College, New York in 1940. Over the following years, the ‘pressure of circumstances’ was often ‘frustrating’. As she struggled to get ‘established professionally in a new field’ whilst raising her children ‘without much help’, Campbell’s life was characterised by the ‘management of precious resources’.

Despite these challenges, Campbell not only survived, but thrived. Familial commitments notwithstanding, her diary was filled with radio talks, committee meetings and appearances before Congress. When the National Association of Consumers was founded in 1947, Campbell featured among the organising committee and was appointed vice-president in 1948. At the same time, she worked on her magnum opus. The Consumer Interest: A Study in Consumer Economics (1949) was a 650-page attempt to confer scholarly credentials upon this embryonic and highly feminised subfield. Conscious that American colleagues still deemed her topic ‘as somewhat beneath their professional considerations’, Campbell sought to counter the notion that consumer economics had relevance only for bargain-hunting housewives. In jargon-free prose, she presented the ‘consumer interest’ as a lens for understanding the totality of economic life.

By 1955, when Averell Harriman, the newly elected Democrat Governor of New York, decided to appoint the nation’s first Consumer Counsel, this Australian-born widowed mother seemed the obvious candidate for the job. In this position, Campbell was tasked with ensuring that ‘the consumer point of view would be taken into account in policy-making’. Consumer education was also a large part of her role, and she developed a national profile through her efforts to highlight the economic significance of the humble act of spending. Campbell returned to Queens College after Harriman was ousted by his Republican opponent in 1959, but remained a figure of national influence. In the 1960s, she went on to advise Presidents Kennedy and Johnson on consumer questions. Campbell also became Chairman of the Queens Economics Department.

From the late 1940s, Campbell resumed active participation in the international sphere. Campbell brought her preoccupation with consumer questions and living standards to bear on the project of international development. This work commenced at the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO). In 1948, 1949 and 1951 Campbell was a U.S. delegate to the FAO annual conference, and served on the Interagency Committee that advised on US FAO policy. By 1949, she was ‘one of the leaders of FAO work’ in the United States, and in this role worked to promote greater emphasis on the ‘question of underwriting consumption levels’ and ensuring an ‘equitable distribution of income’.

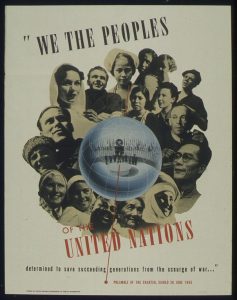

Later, in the 1950s and 1960s, the notion of consumer-oriented development was promulgated through the lobbying Campbell performed in conjunction with the Pan-Pacific and South-East Asian Women’s Association (PPSEAWA), and as official UN representative for the IFUW and the International Organisation of Consumers Unions (IOCU). From 1965, in particular, after retiring from academic life, this erstwhile Australian ‘almost lived at the United Nations’. From her position in the female-dominated ‘twilight zone’ of lobbyists working outside formal diplomacy, she churned out summaries of UN proceedings and reports, penned official submissions to ECOSOC, and made interjections in UN meetings. At a time when rapid economic growth was development orthodoxy, she called for a more consumer-centred approach. ‘It is not enough to get things produced’, she stressed, ‘they must also be gotten into the hand of the people who can use them’. Economic interventions may even do more harm than good. As early as 1953 she warned that ‘rapid industrialisation might worsen rather than improve the social situation’.

This message was not always heeded, but it resounded far and wide. As a leading U.S. economist, her name carried weight both domestically and abroad. At the UN Secretariat, in Washington D.C., and throughout the international NGO community, she boasted contacts, shaped opinion and opened doors. Her role as UN correspondent at the International Development Review in the late 1960s had a particular impact. Campbell became a key intermediary for this journal between the lead broker of development policy and those working on the ground. Her rigorous yet unmistakably partisan articles won ‘a host of admiring and grateful readers’.

By the 1970s, the world had caught up with Campbell. The ‘romance of economic development’ was on the wane, and ‘social development’ became a catchphrase of the Second Development Decade. In a landmark article from 1972, British economist Dudley Seers asked ‘Why do we confuse development with economic growth?’ This was a question Campbell had asked repeatedly since 1948. A generation before ‘poverty alleviation’ came to dominate the development lexicon, she had evangelised about consumer needs and living standards to a global audience of diplomats, bureaucrats and fellow experts. Now, after decades of preaching a dissident message, Campbell found herself, aged seventy-three, suddenly in step with the zeitgeist. But she would not live to see what happened next. In March 1974, in the midst of her usual busy schedule, she suffered a fatal stroke, leaving colleagues around the world bereft. The International Council of Social Welfare, for one, feared that ‘no one can take her place’.

~

To learn more about Australian women active at the UN and League of Nations, visit A Seat at the Table: Australian Women in Global Governance – a new initiative of the University of Sydney’s ARC Laureate Research Program in International History.

Anne Rees is a David Myers Research Fellow at La Trobe University. She is a historian of Australia in the world, and her current research examines Australian women’s transpacific mobility and the impact of United States interwar immigration restriction upon Anglospheric relations. Prior to joining La Trobe, Anne was a Kathleen Fitzpatrick Junior Research Fellow in the Laureate Research Program in International History at the University of Sydney. She holds a Ph.D. from the Australian National University and an MA from University College London, and has been a Visiting Researcher at Georgetown University.

Anne Rees is a David Myers Research Fellow at La Trobe University. She is a historian of Australia in the world, and her current research examines Australian women’s transpacific mobility and the impact of United States interwar immigration restriction upon Anglospheric relations. Prior to joining La Trobe, Anne was a Kathleen Fitzpatrick Junior Research Fellow in the Laureate Research Program in International History at the University of Sydney. She holds a Ph.D. from the Australian National University and an MA from University College London, and has been a Visiting Researcher at Georgetown University.

Follow Anne on Twitter @AnneLRees.

Copyright remains with individual authors who grant VIDA holding a perpetual, world-wide, royalty free and non-exclusive license to use, distribute, reproduce and promote content. For permission to re-publish any VIDA blog post, in whole or in part, please contact the managing editors at auswhn@gmail.com.au