If you venture into the heat and humidity of North Queensland, you won’t only find a history of Japanese migrants. You will also uncover unexpected stories of independent and mobile Japanese businesswomen.

When I began researching the Japanese migrants in North Queensland between 1880 and 1946, I encountered a long-established history of people arriving to work on the pearlshell beds and sugar cane farms of northern Australia. I read these histories about Japanese pearl divers (men) and sugarcane labourers (also men), left wondering what had happened to the women who migrated to north Queensland. As I read on, I discovered that Japanese women often received only a brief mention in these histories. The suggestion was that there were very few who migrated to northern Australia and of these, all were sex workers. Broadly, it seemed, their experiences and contributions had been dismissed.

Archives of government records and newspaper advertisements revealed a very different account, however. Soon I began to question the established history of Japanese women in north Queensland. I found a wealth of stories about Japanese women who migrated to Australia around the turn of the twentieth century. These women were part of North Queensland’s commercial life as independent and mobile businesswomen. Some were involved in shopfronts and stores; others offered services to the community and participated in the informal, neighbourhood economy. The following are just a few of the Japanese women who contributed as business owners, operators and proprietors in early twentieth century north Queensland.

More than just the merchant’s wife

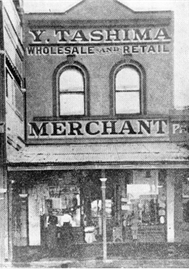

In 1897, Kame Tashima and her husband Yoshimatsu Tashima arrived in Townsville and opened a Japanese fancy goods and curios store named ‘Y. Tashima’. The business held a storefront on Flinders Street in Townsville. It also supplied and traded goods with small Japanese stores up and down Australia’s north-east coast. Over the following twenty years, Tashima’s became one of the largest importers and retailers of Japanese goods in north Queensland.

Women like Kame had more than a minor role in these businesses. Selling items of a ‘feminine’ kind, the presence of a woman behind the counter to offer advice on crepe-de-chines, laces and georgettes was a sound business decision. Women were frequently responsible for the keeping of the store. In some cases, managed the storefront while their husband handled the importation of stock and trade relationships.

Many of the prominent Japanese silk stores around north Queensland were owned by Japanese couples. Such stores included the Oki Silk Store in Innisfail, owned by Chiyoe Oki and Hidewo Oki, and also T. Iwanaga’s Emporium in Cairns, run by Otsume Iwanaga and her husband Tokitaro. These women capitalised on local gender roles that entangled femininity and domesticity with clothing and household items, giving them a commercial advantage in north Queensland’s economic life.

Although we know very little about Kame’s specific role in Y. Tashima’s store, we can conclude she was well-respected among the Townsville community as a businesswoman alongside her husband. The Sub-Collector of Customs indicated in 1913 that both Mr and Mrs Tashima were well-known around town in business and other circles. Indeed, the Tashimas were members of Townsville’s high society; Kame and her husband numbered among the guests at the Japanese Consul Goro Narita’s celebrations at the Japanese Consulate in 1907, while Kame’s husband was elected to the local Chamber of Commerce in 1912.

The widowed laundry proprietress

Life could be much more difficult for widowed women, but Shigi Furukawa seemed to have made her own way as a woman in business. Married twice and widowed perhaps twice, Shigi lived on Thursday Island for twenty years before moving to Mackay in 1918. As historian Catherine Bishop has argued, running a business was a respectable and expected course of action for widowed women. This helped provide financial security and flexibility for those who were unskilled or tied to the home.

From 1926, Shigi ran the Fuji Laundry in Mackay alongside her husband. Shigi was among at least a dozen other married and widowed Japanese women who were operating laundries around north Queensland. These were likely responsible for laundries’ advertised services of mending worn clothes, replacing buttons and tailoring pants.

As Shigi’s husband’s health declined over the years, she probably took over increasing management of Fuji Laundry, until she became the named proprietor following his death in early 1941. The apparent ease with which Shigi assumed control of what was ostensibly her husband’s enterprise suggests that she was already familiar with its operation. The Fuji Laundry’s address was where she both lived and worked. In December 1941, internment records plainly stated that she was a laundry proprietress.

The cafe owner

Kuma Oki was another woman who moved throughout north Queensland as the need arose. Arriving on Thursday Island in 1896, Kuma married a decade later to a pearl diver named Torakichi. The couple had three children together in Australia — Hidewo, Hachiro, and Mary — and Kuma accompanied each of them to Japan, presumably to be educated there.

In 1924, at the age of 47, Kuma found herself a widow. With enough money saved, she relocated to Innisfail and became the owner of a small café on Edith Street, likely located behind another store on that street. Nonetheless, Kuma’s café offered up warm meals — probably noodle-based—to locals and sugar labourers from nearby Mourilyan, taking advantage of their desire for a nice meal cooked by a woman in an otherwise male-dominated environment.

Kuma ran this business for the next 15 years, joined in 1933 by one of her sons — now a successful silk store proprietor himself — and his wife and children. She was now part of a small family network with three businesses between them. Kuma probably helped raise her growing brood of young grandchildren and encouraged her son and daughter-in-law in their business ventures. This small network was perhaps mutually beneficial, growing business connections and a local customer base.

Keeping business in mind

These are just a few snippets of the lives of Japanese women living in early twentieth century north Queensland. Their lives were far more complex and nuanced than the too-often told histories of impoverished and vulnerable women trafficked as sex workers to north Queensland during this period.

In reality, migrant Japanese women in north Queensland were from different classes and had different experiences in business and work. Some were in business with their husbands, others were independent operators, others sold their skills for brief but important periods in their lives. In every circumstance — whether sex workers or shopkeepers; married, unmarried, or widowed; living in regional centres or remote north Queensland — Japanese women made important contributions to the region’s economic and social life.

Tianna Killoran is a PhD Candidate in History at James Cook University in Townsville. Her research project investigates the Japanese migrant community in north Queensland starting in the latter part of the nineteenth century and up to the Second World War. She was a National Library of Australia Summer Scholar in 2020 and has been published in History Australia.

Tianna Killoran is a PhD Candidate in History at James Cook University in Townsville. Her research project investigates the Japanese migrant community in north Queensland starting in the latter part of the nineteenth century and up to the Second World War. She was a National Library of Australia Summer Scholar in 2020 and has been published in History Australia.

Tianna tweets as @tianna_killoran

You can read the full-length version of this article in the 2022 open-access edition of Lilith.

Copyright remains with individual authors who grant VIDA holding a perpetual, world-wide, royalty free and non-exclusive license to use, distribute, reproduce and promote content. For permission to re-publish any VIDA blog post, in whole or in part, please contact the managing editors at auswhn@gmail.com.au